- Home

- Oren Liebermann

The Insulin Express Page 8

The Insulin Express Read online

Page 8

We spent the day walking around the Old City of Jerusalem, seeing an international menagerie of Christmas traditions on display. Some felt oddly familiar. Holiday lights in Bethlehem look much like holiday lights in the States, and they make us feel as if we’re not nearly as far from home as we truly are, separated by both time and distance. Earlier in the day, we caught a Syrian Orthodox parade marching down the narrow, cobbled streets of the ancient city, playing what I can only assume are traditional Syrian Orthodox songs, though how these songs came to be played on Scottish bagpipes I can’t possibly fathom, since it requires an intermingling of cultures that I’m quite sure hasn’t happened yet.

Here in Jerusalem, we even experienced a bit of a white Christmas. A meter of snow paralyzed the city a few days before the holiday, shutting down the streets and public tram system, and though it melted quickly as temperatures returned to normal, the final remnants of the historic snowfall lingered in the most sun-deprived shadows of the city. Of course, that doesn’t compare to the weather back on the eastern seaboard, which is just at the beginning of what will become one of the worst winters on record. We picked a good winter to be very, very far away from home.

We pulled into Bethlehem a few hours ago, sometime in the late afternoon. Technically, I’m not allowed to be here. As an Israeli citizen, it is illegal for me to enter the city, so I carry my American passport in case the border security guards ask. They never do. Bethlehem is a city where it seems anything goes, as long as your ultimate goal is to make a dollar. Or a shekel. The city isn’t big enough or commercial enough to draw major corporate investors, so instead of Starbucks Coffee you have Stars and Bucks Cafe. The familiar green female logo has been replaced by a few cups of coffee and swirling steam, all drawn in the same shade of green.

A festive mood permeates the city, and everyone here is celebrating. The narrow streets are packed with honking cars, and there are even a few Santa Clauses whooping and hollering to the crowds. That all changes when we enter Manger Square. It’s much quieter here, more somber, and smaller than I expected. My impressions of Christmas revolve heavily around my memory of Rockefeller Center. Big tree, lots of lights, a good deal of singing, maybe even an ice rink. Manger Square lacks most of this, especially the ice rink. There is certainly a big tree, but the heavily armed security guards flanking the evergreen—which may or may not consist of far more artificial plastic than natural pine—somehow detract from the festive mood.

The crowd of pilgrims waits for Midnight Mass, passing the time with Christmas carols from all over the world. Since the group is so diverse and their languages so varied, no more than a few people know each song, and these people inevitably stand in a tight circle with their fellow countrymen, so it sounds like the celebration moves around the square in small pockets of happiness. Fifteen Germans sing “Weihnachtslieder” at the northeast corner of the square, followed by ten Finns singing “Joulun kellot” off to my left, and then thirty Ukrainians chime in with “Boh predvichnyi narodyvsia” somewhere to the west.

We find a dinner spot at a tourist restaurant that overlooks the square. The waiter serves up baked chicken in a brown sauce that I’m quite sure would make a distinct slopping sound if dropped from a height of three inches or more. Sometime in the near future, we should be visiting the Church of the Nativity—possibly the oldest church in Christianity—before settling in for a few hours to wait for Midnight Mass. The only problem is that our tour group didn’t anticipate the VIPs that would also be visiting the Church of the Nativity to pay their respects on this evening, which means the church is closed to anyone who’s not Fouad Twal, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, or a ranking member of a government or embassy. That leaves us to while away the time eating dinner and walking around the streets of Bethlehem, with the unfortunate consequence that we run out of stuff to do fairly quickly. Apparently, there’s only so much fun one can have haggling down the price of a pack of gum.

As much as we’d love to stick around for the penultimate Catholic service, we decide to hop on the early bus leaving town at 10 p.m., especially since we’d have to watch the service in a language we don’t understand on a screen we can’t quite see in a city I shouldn’t be in. Latin class couldn’t keep me awake in high school, which makes it highly unlikely that I’ll understand any of what’s being said now, never mind the fact that my religion doesn’t subscribe to the story that the Almighty has or had any offspring to which we should be offering prayers on a holiday that celebrates his birth while missing the actual date by at least two full seasons. Getting a good night’s rest seems the prudent option.

We spend the next few days driving in circles between Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa, visiting my cousins and catching up with everyone. We have no intention of seeing the group of cousins who won’t see us, which works out in a wonderful mutually exclusive sort of way where we can ignore each other in peace. After New Year’s Eve, we make our way down to Eilat, the southernmost point in Israel, for some snorkeling and an overnight trip to Petra, the ancient kingdom in the Jordanian desert. The five-hour drive takes us through the Negev Desert into some of the most inhospitable terrain in Israel. Much of this land is so barren it makes for an excellent bombing range, and it’s not uncommon to see Israeli Air Force jets streaking by at low altitude after dropping practice munitions. On the way down, I gorge on a box of six Krembos.

I cannot adequately describe my love for Krembo, and after my pedestrian description, I’m sure you won’t be rushing to find a package. That’s a shame, since they’re absolutely divine. Imagine a thin cookie, no more than two inches across, with a mound of a substance that’s not unlike sweetened whipped cream, but it holds together at room temperature. Now dip that whole thing in a very thin layer of chocolate. There, you have a Krembo. It comes in vanilla and mocha flavors, and each one is heavenly for its own reasons. Instead of soda or sunflower seeds to keep me awake during the drive, I eat a Krembo every hour or so, waiting until the joy of one has faded and I can no longer resist the urge to eat another one.

Before long, we exit the nothingness that is the desert and enter the gleaming city of Eilat. When my parents honeymooned here a few decades ago, Eilat was the sort of quiet getaway town that people might enjoy. Now, it’s full of glamorous hotels and shopping plazas that make it everything we want to avoid on our world trip. But I still have very fond memories here from previous trips to Israel, and that makes it too much to pass up. Eilat is also one of the best spots from which to visit Petra.

On a free day in the city, we head for a reef and rent snorkels. The water is so salty—far more so than the ocean but not nearly as salty as the Dead Sea—that we float effortlessly, bobbing our way from one submerged chunk of reef to the next. The reefs are divided between adjacent beach clubs, and you access the water via a long walkway that extends over it and ends in three steps leading you into the Red Sea. We hop into the water at one end of the beach clubs, float with the current to the other end, and walk out along another gangway. It’s delightfully easy, and we make the trip a few times, picking different spots over which to float. The water is a bit choppy, and every once in a while a slightly larger wave submerges the end of my snorkel, gagging me with a mouthful of water that contains enough sodium chloride to be very unpleasant. In a few trips along the reef, I drink more than my fair share of the Red Sea.

Even if Eilat isn’t considered one of the world’s greatest reefs, it’s still majestic. On one trip down the reef, I find myself surrounded by a school of fish, completely oblivious to me or to the destruction I could do to their population if I had a fishing rod and some bait. Another school of fish engulfs me on the next dip, until I realize it’s probably the same school of fish being exactly as oblivious to me as they were just a few minutes ago. Still, it’s very exciting the second time around, and I hope that, with their short memory, it’s just as exciting for them.

The air is far colder than the water, so the decision to repeat the same floating snorkelin

g excursion is more a consequence of our desire to stay warm than of being infatuated with the underwater life. Alas, after three trips along the same patch of reef, we decide it’s time to retreat to the warmth of the showers and the changing room.

“You look like you’ve lost some weight,” Cassie says to me casually as we make our way back to our rental car.

“Great! I’ve been meaning to drop a few pounds.” I think nothing more of the conversation, and I barely waste any time trying to figure out how I ate thousands of calories of delicious, chocolate-dipped sugar yesterday, yet find myself shedding pounds today.

The following morning finds us on a bus to Petra. Or, more accurately, on a bus to the Israel-Jordan border and the southernmost border crossing. It takes two hours to hand over our passports, wait for the stamps, retrieve our passports, hand them to someone else wearing a different flag on his shoulder, wait for the stamps, and again retrieve our passports before we’re allowed to hop on an entirely different bus for the drive into Jordan.

If Rockefeller Center determined my predispositions about Christmas festivities, then Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade colored my thinking about Petra. A long, narrow valley in the shape of a crescent moon suddenly opens up into the lost city of Petra, its buildings carved out of the valley’s rose-colored rocks. Inside, we can expect to find a similarly lost seven-hundred-year-old knight guarding a dazzling collection of wine cups, one of which may be the Holy Grail. Drinking from the wrong chalice will find us shriveling away as our hair grows very long and wiry in only a few seconds’ time. Drinking from the right chalice will grant us eternal life. I hope my expectations aren’t too high.

Petra isn’t the only lost city in this region. The Middle East has a nasty habit of misplacing its cities. In some cases, these cities are rediscovered after a few millennia. Sometimes, they remain lost. Take Masada for example. The ancient city by the Dead Sea claimed a group of Byzantine monks as its last inhabitants around the fifth or sixth century. It went missing for the next 1,300 years until it was found in 1838, give or take a few years. Archaeologists rejoiced, and UNESCO added it to the list of world heritage sites in 2001, joining Petra, which was added in 1985. Meanwhile, Ur, the biblical city of Abraham, was abandoned in 500 BC when the Babylonian empire fell to the Persian empire, just as the Iron Age was really hitting its stride. It was AWOL for more than two millennia. By the time Ur was discovered and identified in 1853 in modern-day Iraq, the Industrial Revolution was winding down.

Petra follows this historic if somewhat regrettable tradition of misplacing urban centers. The city was abandoned in 663 AD, forgotten for the next 1,200 years, and rediscovered by Europeans in 1812. Based on this track record, I half expect Atlantis to be waiting for an amateur archeologist armed with a Dora the Explorer backpack to flip over a rock or turn a corner and discover the city somewhere in the Middle East after a few hundred more years have passed.

Our bus driver drops us off at the gift shop that marks the beginning of the trail down to Petra. Gift shops are the universal indicators that something interesting is nearby. Any place of historic value—and quite a few places that have absolutely no value—are marked by a gift shop. The relative importance of the location can be judged by the number of shops, the collection of knick-knacks they sell, and how far away they are from the point of interest. The Great Wall of China, for example, has large clusters of well-stocked gift shops that radiate out quite far from the Wall itself. The Mitchelstown Caves in Ireland, on the other hand, have only one gift shop at the ticket counter that sells the smallest possible collection of postcards.

The first small tent we see sells a bewildering array of postcards, hookahs, and random assorted junk that can only be described as tchotchkes. It is cleverly called INDIEANA JONES GIFT SHOP. They definitely know how to cash in on marketing here, even if the promotions strategy is a bit outdated. We line up with our tour group and follow the signs to the once-lost-but-now-found city. The path to Petra descends through beautiful swirling red rock formations that seem otherworldly in a truly entrancing way. The rock walls of the gorge look like they’ve been shaped and polished by a master of modern art, whirling and dipping with a chaotic sense of beauty. As we make our way toward the ancient city, we begin to see a hint of the buildings ahead. Ancient rock carvings that have miraculously stood up to the withering forces of centuries of wind and sand adorn some of the rock walls, peeking out as if this ghost city is ready to come to life once again.

The final steps through a narrow fissure and into the fabled city are exactly as awesome and dramatic as Indiana Jones makes it seem. The famous rock facade of Petra becomes gradually visible as you inch closer to the site, its full majesty hidden until the very last moment. Its size is breathtaking. Cassie and I spend more than a few minutes staring at the facade, known as the Treasury, even though it almost certainly wasn’t a treasury.

Petra is a wonder of ancient engineering and art, and I think the Nabataeans who claimed the city as their capital had a healthy amount of common sense, some of which I’m sure we could use today. Instead of doing what other city-builders did for thousands of years and moving the rock to the city, the Nabataeans (or at least their architects) realized it would be far easier to move the city to the rock. They didn’t have to carve out stones to build a castle. They simply took the stone that was already formed all around them and carved the city straight into the rock, and they did it in an incredible fashion, with intricately detailed decorations far above ground level. The Nabataeans also built a system of cisterns and floodgates to control the flash floods that occasionally plague the area. They built an oasis in the middle of the desert that stands to this day.

After three hours exploring this wondrous city, the fun part of this trip comes to an abrupt end. Our tour package was supposed to include a night in a hotel. Hotel is a term that conjures up images of warm, neatly made beds and hot showers, possibly even a breakfast buffet with eggs and yogurt. Hotel does not in any way describe the isolated tent city where our bus stops. For a brief moment, I get very excited when I realize we may be staying in a Bedouin village. That excitement soon fades into a mild sort of growing displeasure when it becomes readily apparent that this is, instead, a few cheap tents carefully designed to depict a Bedouin village without, in fact, having any real Bedouin.

The Bedouin are a nomadic desert people known for their legendary hospitality. If a traveler comes by a Bedouin encampment, he will be welcomed in without a moment’s hesitation and treated to endless amounts of water, food, tea, and anything else the village has to offer.

I experienced this hospitality back in college, when I signed up for a Birthright Israel trip, mostly so I could score a free flight to Israel. One of the most unique experiences was a night we spent in a Bedouin camp. I’ll never forget the breakfast they served us. A delectable smorgasbord of fresh pita and yogurt and chocolate milk and eggs and on and on.

It becomes obvious very quickly that this isn’t the sort of hospitality we should expect. First, there is no offer of food and water. Our group, consisting of a few Americans, a Norwegian, and three Italians, has to ask for our meal after sitting at the table for a good thirty minutes being completely ignored by the hosts. After a few more minutes, we realize water apparently isn’t included in the meal, so we have to ask for that too. Second, the only fire, which is also the only source of heat, is a small bonfire burning in one corner of the main tent area. Four or five Jordanians monopolize the space around the fire and its warmth, leaving us shivering in the frigid evening air of the Wadi Rum desert. They pay far more attention to their hookah pipes than to us.

It’s not that I have any problems staying in a tent with Jordanians masquerading as Bedouin nomads. Quite the opposite—a night in the desert sounds pretty exciting and wild, perhaps even a little exotic. My only problem is staying in a tent in the middle of the desert when I expected a hotel.

In the middle of the night, I find myself having to go to the bathroom. O

f course, there is no bathroom in my tent, so I have to walk a few minutes from our semi-private enclosure to the camp’s main area. As soon as I leave the relative warmth of my tent and step outside, I instantly regret my decision. No need to use the latrine is great enough to justify dealing with these freezing temperatures, but having come this far already—all the way to the other side of our tent flap—I might as well finish the journey to the water closet and back.

The bathroom, designed to accommodate the crowds that presumably arrive in tourist season, is a stark reminder that we are in a biblical land. I say that because it appears the flood waters in the time of Noah’s Ark have just now begun to recede in the bathroom. Everything is wet, far too wet to explain with something as simple as “a faucet exploded” or “someone has been showering for three whole days.” Nothing short of forty days and forty nights of constant rain could possibly explain how much water there is in this bathroom, maybe even enough to turn this entire desert into arable land. I relieve myself, shuffle back to bed while skirting around Pacific Ocean-esque formations of water on the floor, and await the coming dawn.

I already knew not to expect a true Bedouin breakfast at this tentpocalypse. But in all of my notes from the trip and all of the other moments and memories I have pieced together from Petra, I cannot for the life of me remember what they served us for breakfast. I suspect this is because of what happened immediately after breakfast when it was time to head back to Israel. Before we leave, which is to say, before we are allowed to leave, we are kindly informed that we have to pay for the water we drank with dinner last night.

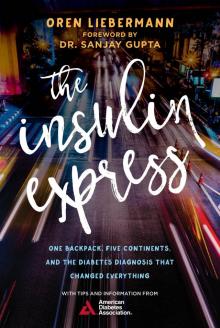

The Insulin Express

The Insulin Express