- Home

- Oren Liebermann

The Insulin Express Page 25

The Insulin Express Read online

Page 25

“Takamoto was beautiful,” my mom says, and I have no idea if she means Takayama or Matsumoto.

“Yes, so was Matsuzawa,” my dad responds, creating some hybrid city of Matsumoto and Kanazawa.

“Just like Kanayama.”

I don’t know if they’re referring to the first half of the city or the second, so I politely smile and nod. Maybe Japanese efficiency has caught up with them and they’re simply complimenting two cities at once.

We conclude our Japan wanderings in Kyoto. Kyoto is what I expected Tokyo to be, though the confusion is due entirely to my own ignorance and not at all to the city planners who created two diametrically opposed urban environments with names that are anagrams.

Where Tokyo is full of stylish skyscrapers and bright neon lights, Kyoto is replete with ancient Buddhist temples, stunning Japanese architecture, and myriad costumed geishas. We visit too many temples to describe any specific one in great detail, but I do stumble across the grown-up version of something I used to sell.

Back in high school, I spent my senior year working at a store called Natural Wonders. It sold a random collection of science experiments, nature-themed T-shirts, and telescopes. It was a horrible concept for a store. One day, we even registered negative sales, an accomplishment that was only possible because someone made a huge return and we barely sold anything. The only neat thing we sold were ecospheres. They were little enclosed glass baubles that had a few brine shrimp—more commonly known as sea monkeys—swimming around happily in their clear spherical cage. I bought one for my girlfriend. It didn’t last long, and here I am referring to both the brine shrimp and the girlfriend.

On the counter near our registers, we sold Zen gardens. The package, which was entirely overpriced at fifteen or twenty dollars, consisted of a small, flat container, some sand, a few stones, and a neat little wooden rake, perfectly sized if a squirrel encountered the sudden urge to do some yardwork. I never quite understood the name at the time, since nothing grows in a Zen garden, and it doesn’t seem to inspire a feeling of Zen.

I still don’t understand it now, looking at one of the most famous Zen gardens in the world in the temple of Ryoan-ji in northwest Kyoto. A temple has stood on the grounds of Ryoan-ji since the eleventh century. The temple has been torn down and rebuilt a few times—most recently destroyed by fire in 1779—but its most striking and famous feature is the eponymous Zen garden. Historians disagree on when the Zen garden was added to the temple, but estimates put it anywhere between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is at least a hundred years older than America. Ryoan-ji is considered one of the finest examples of a dry landscape garden.

It is a rectangle of 248 square meters with fifteen rocks in three groups spread out between white gravel. The gravel is meticulously raked every day by the monks. As with any piece of art, there is a wide variety of explanations for what the garden is supposed to represent: islands in a stream, mountains poking out above a layer of clouds, swimming baby tigers, and the list goes on. Sitting on the platform that faces the Zen garden and meditating is supposed to inspire a state of inner peace and concentration.

None of this happens to me while I am staring at the gardens and taking pictures. Part of the problem is the swarm of teenage kids that are careening around the garden, doing very un-Zen things like talking and laughing. But I think most of it is that I’m not properly Zen enough, even though I’m not quite sure what that means. I think this applies to my family as well. Cassie stands by me only because I’m busy taking pictures. My parents take a brief look at the garden and keep moving. And then we are on to the next tourist spot. In fact, the most distinctive memory of the Zen garden is the flashback to my old job.

After a few more days in Kyoto, we part ways with my parents. They have a flight home from Kyoto, while we fly back to Tokyo to catch a flight to San Francisco.

San Francisco may seem a strange place for an American to visit on a trip around the world, but consider this. Our flight from Bangkok, Thailand, to Kathmandu, Nepal, took four hours. A flight from New York to San Francisco takes five hours. It’s not exactly a weekend trip. So we take advantage of being on the Pacific Ocean to visit some friends in San Francisco, and Cassie’s parents decided to take a week off to meet us there to go romping around wine country in Napa and Sonoma Valleys.

Our flight to San Francisco, to American soil once again, is an easy flight on an easy day. Or at least it should be. We wake up late, have a standard Comfort Inn breakfast in Narita, then head for the airport with plenty of time to spare, which allows us to peruse Japan’s bewildering array of Kit-Kat flavors. We buy some Red Bean Kit-Kats, some strawberry cheesecake Kit-Kats, and some pudding Kit-Kats, and head for check-in for Flight 838, only to get a perplexed look from the ticket agent.

“Flight 838?”

“Yes, 838 to San Francisco at 3:50.”

“Flight 838 to San Francisco at 3:50?”

“Yes, Flight 838 at 3:50.”

This went back and forth for some moments—me naming the flight number, destination, and time in a definitive statement and her repeating the flight number, destination, and time in a question. The intonation in my voice went down at the end of the sentence, and the intonation of her voice went up.

“Flight 838 to San Francisco at 3:50?”

“Yes, 838. San Francisco. 3:50.”

“Oh, your flight was cancelled. Please wait in this line for help.”

Cancelled? I’m so stunned, I don’t even blow up at the lady. A quick check of the departure board confirms this horrible bit of new information. The airline cancelled our flight without giving us any warning. No email, no phone call or text message, no nothing. Thankfully, there are only about six people in front of us in line, so we should be on the next flight to San Francisco, leaving a short time later, right?

After ninety minutes of standing in line, our planned trip to the United States seems to include one more unplanned night in Tokyo. I am ready to blow a gasket and I kindly inform a hapless airline employee that she is a fucking idiot when she tells me I have to use a pay phone to call the reservations line for her company when it is her company’s decision to cancel the flight that forces me to make the call in the first place. The Japanese rarely speak loudly, and if I had to guess at their average decibel level, I would say it’s somewhere in the sixties. I have surpassed that exponentially, and I wonder if I could apply for the loudest person ever in Japan. In a country renowned for its intelligence, I conclude I am surrounded by idiots, and I try to yell at as many of them as possible, which makes me feel inestimably better while advancing our position not at all.

Cassie, employing a strategy that is completely foreign to me, is nice to a different agent and is allowed to use a company phone for free. Moments later, she informs me that we have the last two seats on the next flight out of Tokyo for San Francisco.

Two things amaze me about this entire debacle. First, that a Twitter message Cassie sent to the airline is far more effective at getting us a new flight than a small army of airline contract workers at Tokyo’s Narita International Airport. The airline’s social media team responds with a phone number, and, somehow, Cassie does in one five-minute phone call what five airline workers in Tokyo are completely unable to do in an hour and a half.

Second, it seems we will not have a headache-free trip back to the States. Our last flight home involved a five-hour delay, of which three hours were spent sitting on the tarmac at Baltimore-Washington International Airport. And now the airline cancels a flight and hefts upon us a veritably incompetent group of airline employees, in what can best be described as adding insult to injury. Okay, rant over. But be forewarned. Our problems getting back to the United States have not ended.

We land in San Francisco twelve hours before we took off, in one of those strange time-space paradoxes that always happens when you cross the international date line from west to east. Back on American soil, we head straight for a pharmacy and purchase in four minute

s what I couldn’t find in four countries: a blood sugar monitor that uses the seven hundred blood sugar test strips I have been carrying around.

Then we do what we do best. We head for Napa Valley and drink wine.

A week later, after spending time with friends and family, we board a plane for South America.

Chapter 22

June 12, 2014

13°15’51.4”S 72°26’50.3”W

Machu Picchu, Peru

“No one died at Dead Woman’s Pass,” our hiking guide, Mike, tells us at dinner, in what I suspect is a tone of voice meant to reassure us. “No one died there. It’s called that because it looks like a woman lying down. But Lying Down Woman’s Pass isn’t a good name.

“So … Dead Woman’s Pass,” Mike says, before he helps himself to more rice. He claims he would be thin if they didn’t serve such good food on the trail.

We are having our first dinner on the Inca Trail, a four-day trek to Machu Picchu that will take us as high as fourteen thousand feet before we descend into the ancient Incan city. The fact that Dead Woman’s Pass has not killed anyone is of little comfort to our exhausted group. We all feel dead, which, as far as we’re all concerned at this particular moment, is much the same as being dead. It’s only day one, and we’re wiped.

After my diagnosis, I began to view the Inca Trail as one of the most significant parts of the trip for me. Above all else, it is a big fuck you to my diabetes, much as the Great Wall of China was, but on completely different scales. The Great Wall was one night away from civilization and medical care. This is most of a week.

The last time I took on a hike of this magnitude, Cassie and I were in the Himalayas, and the hike almost killed me. Now I am determined to complete this hike to prove to myself—and maybe even to others—that I will not accept any limitations on my life. I control my diabetes. It does not control me.

We meet our hiking group the night before the trek. Fifteen of us, mostly Americans with some Brits and an Aussie tossed in for good measure. Though we are an eclectic mix at first, our guide promises us we will be a family by the end of the hike.

I check my email one last time before calling it a night and see a message from my dad.

“You don’t have to be brave. If you don’t feel well on the hike, you can stop and turn around. Love, Aba.”

It is a nice note, but I delete it almost immediately. I know with absolute certainty that I’m going to do everything it takes to finish the hike, and I’m sure he knows it too. I am willing to put my life at risk once again to make a point.

We set off at five the next morning, settling into our seats for a ninety-minute bus ride to the starting point of the Inca Trail. We grab a small breakfast somewhere along the way—nothing special, but enough to tide us over until we stop for our first snack break. I buy a small bag of coca leaves, the raw material from which cocaine is made, to chew during the hike. Our guide says they help with the altitude.

“Take bits of charcoal, wrap them up in coca leaves, and start chewing.” I stuff my bag in my cargo pocket and make it a point to break out the coca on the tough climbs.

At the starting point of the hike, Mike gives us one final pep talk.

“Remember to go slowly. And let us know if you need help.” A moment’s hesitation. “Packs on!”

Mike pulls me aside. I know what he is about to ask.

“Uh … I saw that you are diabetic. Will everything be okay?”

“Yes, I promise you. Everything will be fine. And if the shit hits the fan, Cassie knows exactly what to do.”

“Good!”

I think he is reassured that I have a backup plan and relieved that he is not a part of it.

Our group takes a photo by the CAMINO INCA sign that leads to the first checkpoint and the trail. Then we begin. Within minutes the path immediately ascends. Mike had warned us earlier. Today we will climb for ten minutes right at the beginning. Tomorrow we will climb for four hours. Better get used to it now.

In the higher altitude at seven thousand feet, we are all breathing hard after only a few steps. Our porters—called chasquis (runners) in Quechua, the native language of Peru—fly by us, effortlessly moving faster while carrying more. We plod along, sucking in every bit of oxygen within vaccuuming range of our lungs.

I push myself because I can. There is no weakness holding me back, no overwhelming thirst slowing me down. Mike prods us all along with cheery phrases like “Easy peasy, lemon squeezy” and “Hola hola, Coca-Cola.” These corny idioms become our mottos, and we shout them out as we crest each successive hill, fueling our tired legs with positive energy, which doesn’t work quite as well as calories but is a passable substitute until the next snack break.

The first day is the easiest day—not easy, but easier than the other days of the hike. We don’t climb too much, and we don’t walk too much. About seven miles of hiking over eight hours. We all know what awaits us on day two—Dead Woman’s Pass, a brutally steep climb up to 14,000 feet, followed by a sharp descent back down to 12,500. By some geographical coincidence, the highest point of Dead Woman’s Pass is almost exactly as high as Annapurna Base Camp. At least in theory, the challenge of the climb will be almost exactly the same.

Day three isn’t a test of strength. It’s a question of endurance, a ten-mile marathon of hiking that will take us twelve hours. We have to climb two mountain passes—neither as high as Dead Woman’s Pass but difficult nonetheless—and the rest is Peruvian flat, which is a polite way of saying an endless succession of rolling ups and downs.

Cassie and I move well on the first day, normally within a few steps of each other. Breathing is often difficult, but we catch our breath after a few seconds. It feels great to be here on the Inca Trail, inhaling cold, crisp air as we work our way higher into the Andes.

At dinner that first night, we all begin to get to know one another, swapping stories of where we came from and dreams about where we’re going. Chris and Ali—a Scot and an Aussie—are on an extended trip like ours, except they did a lot more skiing. Their next stop is Brazil to see four World Cup matches. After the trek, they take an overnight bus from Peru to Brazil for their first match, and by the time they get off the bus, both England and Australia have been eliminated.

Jim and Cristin—two Americans from New York—are on their delayed honeymoon. They took six weeks off to tour the Pacific Rim. Their next stops will be Buenos Aires, then Sydney. Then there’s Dane and Francois—two friends from Missouri who decided it’s time for an adventure together for some camaraderie and maybe even a bit of soul searching. And the list goes on. Fifteen different stories from fifteen different people sharing one hike on the Inca Trail.

As I climb into my sleeping bag that first night, a realization hits me. The last time I used this sleeping bag, I was in the first hospital in Nepal. It was during my darkest hours. All sorts of memories come flooding back about the Himalayas trek, the week I was diagnosed, the time in the hospital, and how much Cassie helped me through every minute of those days.

These are painful memories; they will always be painful memories. Now they are still raw, and the emotional scars haven’t formed yet.

Cassie is already asleep, but I reach over and place a hand on her arm. She was my rock then, and she is my rock now. I wish I could slide closer and hug her, but she needs her rest. I do too, but sleep suddenly becomes elusive. There isn’t a sound in our campsite, and I lie awake in bed, waiting for my eyes to close. Even the simple act of trying to fall asleep reminds me of the hospital in Nepal, when Cassie would leave at night to send emails to my family, and I would be left alone. Once again, I have no way of tracking the passing time. I slow my respiration and count each breath, trying to figure out how many times I exhale in a minute. Remembering the cramps from the Himalayas, I try to stretch my legs in my sleeping bag.

At least now Cassie is right next to me. And I am feeling great, energized by the physical effort of the hike and the beauty of the surroundings. Easy peas

y, lemon squeezy.

The wake-up call comes at 5:30 in the morning. A chasqui knocks on our tent—insofar as one can knock on a soft piece of nylon—and whispers, “Buenos dias. Coca tea?” The hot drink is a welcome start to the day after a cold night.

Breakfast is a rushed affair with only one cup of coffee, not the necessary seven if I’m to function properly any time before 6 a.m. We hike in the pre-dawn light. A short, flat section first, and then we begin the climb to Dead Woman’s Pass. As we begin the push, it occurs to me that I might as well be in Nepal on the Annapurna Base Camp trek. The Inca Trail has the same uneven steps, the same altitude, and, although far from significant, the same color dirt. At least it’s not snowing or raining.

We hike under beautiful blue skies, letting the sun warm us even if the air is quite cold.

The air is getting thinner, and we can feel it. We rest often, each time a few moments longer than the one before. I pull out my bag of coca leaves and start chewing, following Mike’s instructions. This is the closest I have ever come to doing drugs—chewing on dried leaves and charcoal while hiking in the Andes. I don’t know if the coca leaves help, but at least they give me something to do while we climb.

I am tired as we trek, but unlike Nepal, I am not exhausted, and I am not cramping. There is no feeling of weakness, no perpetual thirst, and—thank God—no need to run to the bathroom every hour. If I test my blood sugar and it’s low, I eat one of my stash of Snickers bars I have or take one of the glucose gels. With all the trekking and climbing, my blood sugar never gets too high.

It feels awesome to be up here, even invigorating. It is one more step in living the way I intend to, not the way diabetes forces me to. Inevitably, I have to answer all the usual questions as our group sees me taking insulin shots, but it’s great to hear the good for you’s and the it’s awesome that you’re still up here’s from everyone. On the Inca Trail, we support one another, applauding as everyone reaches the campsite and wishing each other good luck on the next stretch.

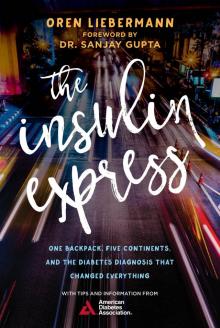

The Insulin Express

The Insulin Express